A sunset glow sweeps over the exquisite façade of San Michele in Foro, surely one of the most beautiful churches in Italy. I sip an Aperol Spritz and watch old and young negotiate the cobbled streets on clapped out bicycles.

People scurry past the cafe, clutching flat, square boxes from the most popular pizzeria in town. If I strain my ears I can hear a rendition of the opera La Boheme being played from Puccini’s birthplace in the nearby piazza, now a museum.

At dawn, the next day, I walk along the ramparts that completely circle the centro storico. Only the early morning joggers disturb my view over the terracotta roofs and bell towers of medieval and Romanesque churches. I stroll along Via Fillungo, the exclusive shopping street, searching for silk – silk scarves, silk underwear, silk anything. Lucca has prospered since Roman times but its heyday was from the 11th to the 14th centuries when this exclusive fibre brought wealth and power to the town. Silk, and high quality olive oil, is still the reason this graceful, tranquil town prospers today.

But Lucca can be lively too. As I walk towards the oval shaped Piazza Anfiteatro, built on the site of a Roman amphitheatre, vintage cars pin me against the wall. The cars race through one arch, circuit the piazza, shaking medieval houses to their foundations. Then they roar through another arch and along the narrow streets filling people’s lungs with gasolene.

I head towards the Piazza Napoleone and the Duomo de San Martino. Here the area is packed with market stalls selling pasta of every shape, gelato of every colour, pesto with everything. People rummage through piles of second hand clothes, overturn old paintings, hoping to find a bargain. One market trader sets out his African statues, sits back and waits for custom. I approach the Duomo de San Martino but am stopped at the doorway. I look up at the carvings above the doorway, peer round the pillars and glimpse the stunning atrium. Women, their heads covered, shuffle past me, up the aisle and towards the priest.

I walk back through Piazza Napoleone to search for a building that doesn’t feature in any tourist guide. Nor have the officials I ask in the Palazzo Ducale ever heard of it. When I get to the Museo Paolo Cresci per la storia dell’Emigrazione Italiana the building is closed and there is no sign of when it will open. The waiter in the café opposite takes pity on me and I down a few cups of espresso, hoping for some sign of life.

I walk back through Piazza Napoleone to search for a building that doesn’t feature in any tourist guide. Nor have the officials I ask in the Palazzo Ducale ever heard of it. When I get to the Museo Paolo Cresci per la storia dell’Emigrazione Italiana the building is closed and there is no sign of when it will open. The waiter in the café opposite takes pity on me and I down a few cups of espresso, hoping for some sign of life.

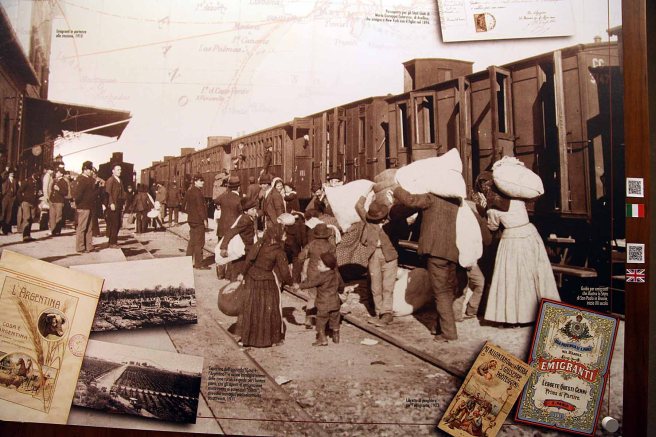

At 3pm the door opens. I enter the circular chapel of San Maria della Misericordia with frescos above of Mary riding a cloud set against the sky. A trunk and ‘fagotto’ bundles of cloths reassure me I have found the right place. There are panels on every inch of wall space covered in photographs, other printed material and text – in Italian of course.

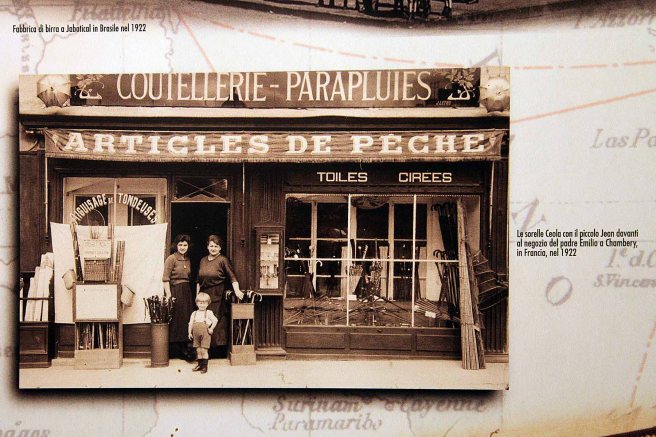

But the visual material is not difficult to read. A struggling peasant family stare into the camera. People board a train or a steamer, weighed down with their possessions. The Statue of Liberty graces every postcard sent home. People pose in their new homes – in tenements in New York, the pampas in Argentina, a house with a garden in the Chicago suburbs or newly found villages in Brazil. Proud owners stand outside their shops in America or France selling fishing tackle, umbrellas or coffee. Muscular men dig mines in Belgium, construct roads in Romania, cut sugar cane in Australia. Women work as wet nurses or run boarding houses for other émigrés maintaining their role as, ‘angel of the house’. Men, women and children work together in a brickworks in Brazil.

In Glasgow street vendors sell ice cream in summer and, ever adaptable, horse chestnuts in winter. Itinerant craftsmen sell plaster statuettes in Paris. Studio portraits of confirmations or crowd scenes of festivals in north and south America show how migrants hold onto their Italian identity. Others, in fashionable attire, suggest an enthusiastic adoption of the American dream.

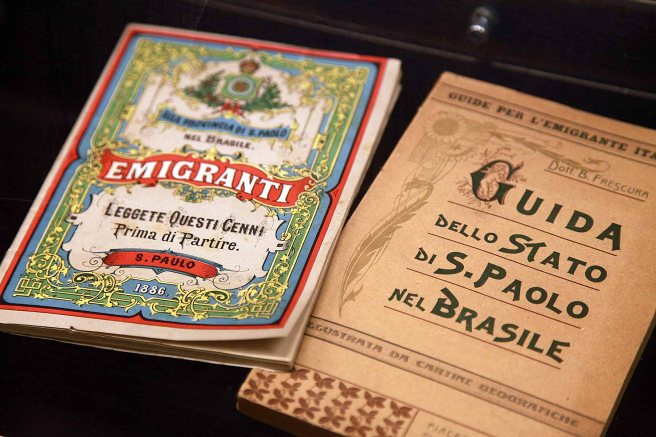

Emigrant booklets attract labour with images of an earthly paradise abroad, lush vegetation and even lusher houses. But dramatic pen and ink images on the front covers of journals of A Tribuna or Il Secolo Illustrato tell a different story. Italians die in a mass brawl in 1896 at Aigues Mortes in France.

A young image maker, Borelli, in 1903 is beaten up by passers by who destroy his basket of statuettes. But there are positive, rags to riches stories too. Guiseppe Giorgi started working as a labourer in Brazil but ended up owning a successful railway company. Raffaele Rossi, who emigrated from Lucca with his family in 1875, set up the town of Caxias, again in Brazil with settlers from Veneto.

At the end of the exhibition there are two panels dedicated to immigration. The images are recognizable, universal even. Illegal migrants embarking from a boat, a smiling fruit and vegetable seller, a demonstration by turbanned Sikhs and women working in sweatshops. But how frustrating that I can’t read the text.

It is only on my second time round of this quite traditional display that I realise I can scan QR codes with my Iphone and down load the text in English. Only at the information desk by the section on immigration do I discover that the Museum has an English booklet. Perhaps this will tell me why this elegant town in a prosperous agricultural region has a museum of emigration

I return to my friendly waiter opposite for yet more espresso and to read the pamphlet. I learn that Paolo Cresci collected 15,000 photographs and documents over 25 years from the families of emigrants, other collectors and antique markets in the province of Lucca. He worked as a photographer at the University of Florence and held a few exhibitions locally. But he was also one of the main contributors to the exhibition, The World in my Hand – Italian Emigration between 1860 and 1960 held in New York in 1997.

I read about the laudable aims of this unsung, hidden museum. Not just to provide statistics and collective and individual migrant stories, but ‘to encourage a welcoming and tolerant frame of mind’, that emigration, but also immigration, provides. I turn to the pages on immigration. I learn that the number of immigrants to Italy has increased ten fold from 1990 when it exceeded half a million. That the open minded initial laws on immigration have been replaced by mistrust. That Romanians are the largest immigrant community followed by Albanians and Moroccans. Most immigrants live in north and central Italy. They account for 11.5% of Italy’s GDP; fill permanent shortages in the fields of the elderly and family home care, agriculture, construction and nursing and keep the Italian National Welfare and Pensions Agency afloat. 4000 thousand work as entrepreneurs or as directors or shareholders in companies. I learn that in Milan Egyptian pizza makers outnumber Neapolitan ones.

As Galbraith said, and is quoted in the booklet, “Migration is the oldest action against poverty. It selects those who most want help. It is good for the country to which they go: it helps break the equilibrium of poverty in the country from which they come. What is the perversity in the human soul that causes people to resist so obvious a good?”

So if you need a break from straining your neck to see the fine mosaics on the façade of San Frediano or want to learn more of the lives of people not represented in the splendid Palazzo Mansi then pop into this small museum. But be sure to pick up the English booklet at the information desk placed at the end of the exhibition. Or get IT savvy, and download the whole exhibition on your Iphone. Either way make sure you pop into the restaurant for an espresso or something stronger on the way out. I recommend the Aperol Spritz.

Museo Paolo Cresci Museum of the story of Italian emigration is on

Via Vittorio Emanuele, 3

55100 Lucca

Enjoyed reading this article Eithne. Fascinating stuff on Museum of migration. But somehow plight of so many current migrants seems so desperate.

LikeLike

Hi Hajra

Yes I know and UK’s response is lamentable. More on this when I reach Sicily and Lampedusa.

Thanks for your interest and see you soon.

Eithne

LikeLike

This is absolutely lovely Eithne!

Thanks for sharing? Xxxxx I fell in love with Venice a few weeks ago, and Florence back in January, Italy is finally working it’s charms on me as well. hope,you’re well and enjoying your travels and writing. X

Date: Fri, 29 May 2015 13:26:00 +0000 To: rosie@stylishshots.com

LikeLike