The pressed flowers and leaves, picked by Bob and his mother when she came to visit him in a Hampshire orphanage, are numbered and named. ‘ The most precious thing I had were my scrapbooks,’ reads the caption in the Children’s Journeys gallery in Sydney’s Maritime Museum. ‘ It was the only link with my mother.’ Bob was illegitimate, the result of an affair his mother had when her husband was serving in the Second World War. In 1952 Bob was sent to Fairbridge Farm School in New South Wales.

I watch the film about Bob, as an adult, revisiting a now derelict Fairbridge Farm. Bob never saw his mother again and only in 2000 did he get access to files and learn his father’s name. It is a moving film but it is the scrapbook that, in Roland Barthes’ words, ‘pricks and bruises’ me.

Brian Bywater’s situation was different from Bob’s. In 1955 he made up his own mind to go to Australia as part of the Big Brother Movement set up in 1926 to give young people the opportunity to work in the outback.. ‘I don’t remember feeling any sadness. The tears were all on their side.’ There is no sign that Brian ever regretted his decision.

Darren Byrne went to Australia at the age of ten as a Ten Pound Pom in 1976. ‘My parents could not believe our cabin – it had a desk, its own ensuite and a bonus two portholes. It seemed too beautiful for migrants.’ Darren got up to all sort of pranks – breaking portholes and ignoring the ‘Crew Only’ signs to explore below deck. When his family arrived in Australia they stayed in Graylands Migrant Hostel until his father found work.

Dao Lu, aged four and Dzung Lu, aged six, left Vietnam in 1977 on Tu Do, a boat made by their father. Dzung was left behind in a swamp but Tan, their father, against the wishes of others in the boat, went back to fetch her. ‘The sea was completely black I remember staring at the little lamps the only thing we could see in the night. They made me feel very cosy.’ The 39 passengers escaped Thai pirates, and with only the help of an atlas torn from a school desk, arrived safely in Malaysia..

But the refugees had little success with the US immigration authorities so 31 set sail once more. They landed in Darwin.

I watch a film of Dao and Dzung relaunching, Tu Do outside the Maritime Museum. I go outside and find it anchored alongside other, larger boats. Even within the relative quiet waters of Darling Harbour Tu Do rocks, the decking on which I’m standing rocks and I feel queasy. 6000 miles with 39 people in such a small boat!

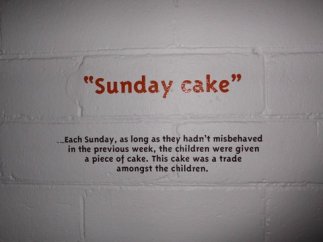

Burnside Museum, opened in 1997, aims, ‘to provide the community with a rare insight into what it was like to grow up in Burnside homes – the fun times and the sad times.’ Burnside Presbyterian Orphan Homes was set up in 1911 to house deprived children, ‘ in cottages in self-contained villages rather than in barracks-style accommodation.’ The pictures of the different buildings, some like mini Scottish castles, are impressive.

But Burnside children, past and present, were, as far as I know, born in Australia so I am curious as to why a friend in London, who did an artist residency at Burnside, has recommended a meeting with the archivist. The Museum, on the outskirts of Sydney, is closed for the holiday so, at Lindsay’s suggestion, we meet in a Turkish café in funky Newton. Lindsay talks eloquently about the importance of the Museum to past residents and their families. But how does this relate to my research on child migration?

Then Lindsay pulls out a large packet. “Since I got your email I’ve been doing some research.” We pour over photocopies of documents from the Burnside archives, ignoring the Turkish music in the background. At the height of the tensions in the 1920s Irish Republican troops burnt down an orphanage of Protestant boys in Ballyconree, County Galway. They considered it a, ‘ a nest of loyalists’ as a number of ex-boys had fought in the British army in World War One. The boys were given 10 minutes to get out of the orphanage and were locked in the church whilst their home and possessions were burnt to cinders. The boys were evacuated to London by a British naval destroyer. Months later 22 of them, aged five to seventeen, sailed to Sydney on the Euripides, a trip sponsored by a Scottish born wealthy Australian. The children were welcomed at Sydney Harbour on December 23rd 1922 by the Chairman of Burnside, a Colonel Murdoch. ‘This is a land where prerogatives of birth do not obtain no matter how lowly or humble your birth.’ The children join in the Burnside festivities, receive presents from the Christmas tree and are given a lucky shilling on their road to prosperity. So what happened to the Irish evacuees? The Story Of Burnside, published in 1947, states that, ‘most of them turned out fine, successful boys: they became good Australians without ceasing to be Irish.’ In 2012 a photograph of the boys at the home in Galway, before it was torched, appeared in the Irish Times. It was sent by Susan Farrell, daughter of Albert Farrell who travelled on the Euripides. Susan was keen to trace her ancestry. According to Susan her late father described his time at Burnside as a,’ new heaven and a new Earth.’ This coverage prompted Elaine White to share information about her father, Walter Horace Millar. He was one of six that was sent directly to work on a farm. He lived happily with the Murphy family who ran a sheep station in Queensland, joined the air force, contracted TB, married a nurse and died early in 1952 when Elaine was five. But what of the other 20?

In 1939 13 boys and 4 girls, aged 5 – 12, from Quarrier Homes at Bridge of Weir near Glasgow, were sent to live at Burnside. Many were not orphans but, ‘born out of wedlock when it was unacceptable for them to be acknowledged.’ I read the unauthored report. ‘As children many of them accepted the proposal of coming to Australia thinking of if it as an exciting boat ride without understanding either the distance involved or that they would not be returning to Quarrier homes.’.The report continues. ‘Most assumed they had no family… The resulting loss has caused immense grief and loss of identity .of these Scottish children and affected their lives in untold ways.’ Some children were later reunited with family members but, as the report tellingly states,‘ the hurt can linger.’ Lindsay has one last surprise for me. A New Life, describes how Australia accepted 51 young people, aged 13 – 18, who were taken away by Khmer Rouge when they were 7 or 8 years old and used as slaves. When the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia the Khmer Rouge ran away and the children walked to refugee camps in Thailand. In 1983 Burnside took on responsibility for 28 of the young people taken in by Australia.. The report explores whether fostering with fellow Cambodians, group homes or independent living was the best support system. Stories of a murder of one young person by another, attempted suicide and tracing families to see if they survived, make gruelling reading. But there are positive stories too. 13 of the young people marry and recreate families in their new home. The author is optimistic. ‘ There is a strong sense that the horrors of the past have lost their sway … and that young people are now freer to build positive new lives for themselves.’ But where are voices of the young people themselves? After our meeting Lindsay sends me images of the Museum and writes, ‘Your visit has spurred me on to plan an independent display relating to the child migrants. I will keep you informed of my progress.’ I can’t wait.

See www.anmm.gov.au for more details about the Maritime Museum in Sydney. On their Own, an exhibition about British child migrants sent to Australia is at present at Liverpool Maritime Museum. It will be on at the V&A Museum of Childhood from Autumn 2015.

Hi Eithne, enjoyed reading your post about Sydney. Bob’s scrapbook is also one of my favourite objects at ANMM – so powerful.

LikeLike

Hi Kim

Really interesting that we are drawn to the same object. I think it’s because it was something that Bob and his mother made together, an activity they both enjoyed.

Did Bob ever find his father?

LikeLike